american business logic

how you do what you do, and why you do, how you do

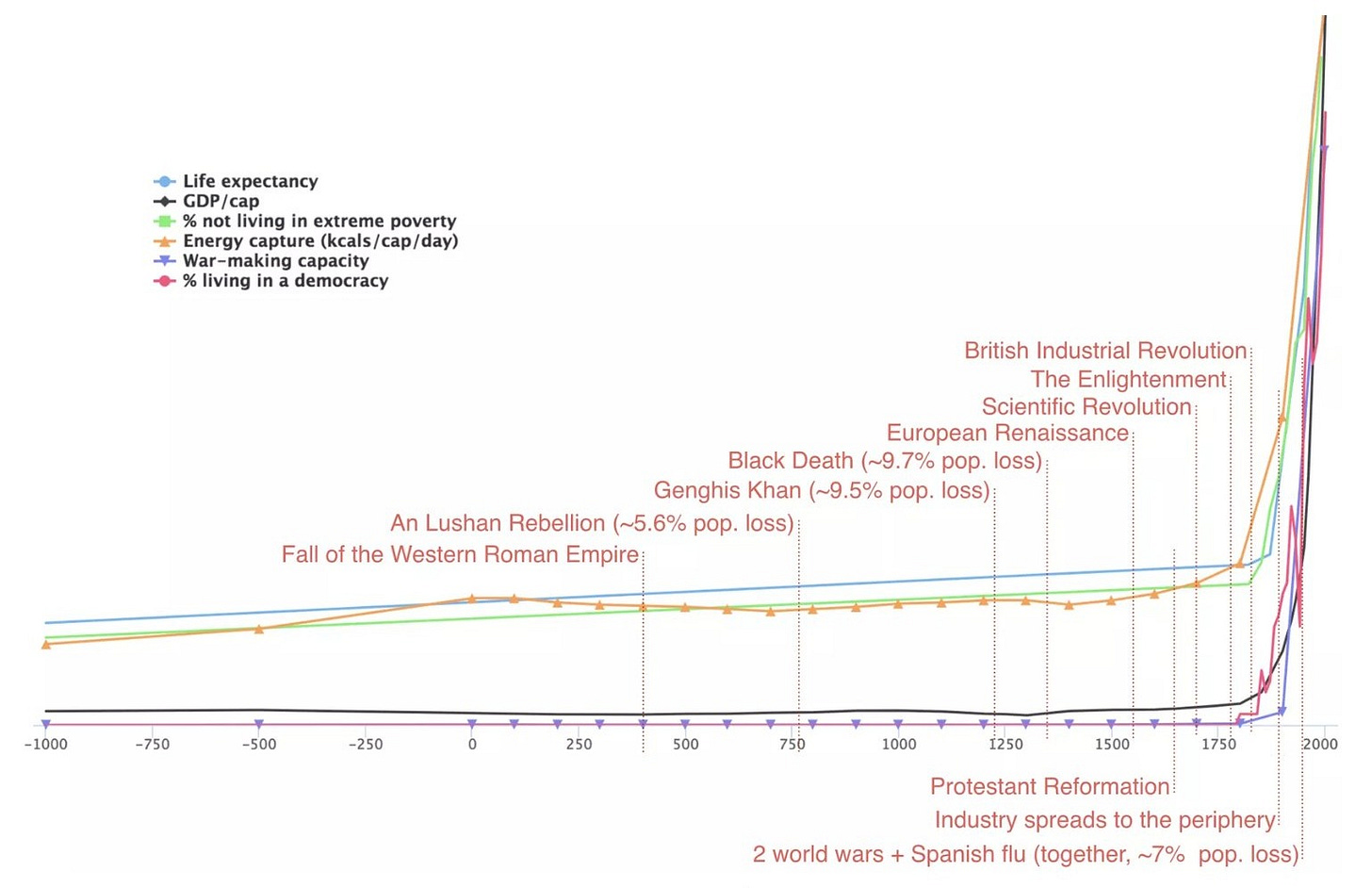

abstract; i start this piece with a napkin sketch history of management. i describe the activities that inform the theory that informed 20th-century practice (aka how mgmt was done) and the theory that shaped 21st-century coordination infrastructure. i argue that systematic pressure conditions and space-time divided 20th-century mgmt practices into two operating worlds: the serious world and the unserious world. i then claim that the coordination ideas (aka yc startup advice) driving the saas movement emerged as a reactionary stance against the unserious world and the bureaucratic models of taylorism. i claim yc and co paired eliyahu goldratt’s just-in-time principles with a new set ideas for conceptualizing 'doing.' these ideas were both (a) shaped by pressure conditions that demanded the lowest level of accuracy in human coordination and (b) fundamentally transformed how we work, how we coordinate, who we coordinate with, and what we work on—within an unprecedented amount of space-time. i elucidate this hidden framework of how we do things, name it american business logic, and describe its implicit rules encoded in the definitions of basic words. i examine how the 20th century myth of tools as value-neutral led to productivity surges in specific context windows but in aggregate led to a complete collapse of human coordination abilities. i claim the world we live in to be the actualized version of a post-agi future in which humans have a coordination capital market crash and have lost the capacity to control and regulate against the runaway effects of technological and abstract machines.

‘tech criticism seems to have entered an end-of-history phase as one long, exhausted, defeated terminal grumble of desultory jabs, devoid of both the sharp insight you reluctantly had to acknowledge in the past, or the combative vigor you felt compelled to defend against for the sake of techie honor. It is well-complemented by tech positivism entering its own red-pilled end-of-history phase as a shrill, ragged screech of derpy self-soothing about great men, doerism, first principles, etc. you can safely ignore both at this point. neither has anything interesting to say about technology qua technology. only dull things about each other. caricaturing each other to death.’ — venkatesh rao

brief history of management

before i start with a history of management, it perhaps makes sense to ask what even is a history of management? what it is, is a function of the size we assign the concept that is ‘history of management’. if we go small, then we’re zooming in on the 20th century, the lean movement, taylorism, goldratt’s just-in-time principle, things of that nature. if we expand it out and define the history of management as the history of people coming together to achieve complex goals then we start to include things like war — jomini’s theory of war was different then von clausewitz’s and so forth. if we really expand and honor the textbook definition of management as the process of dealing with or controlling things or people then we’re really looking at is coordination at large. for the sake of this piece, i’m going to stay small and focus on recent 18th century and forward.

if one wants to learn about the history of management from a war perspective lawrence freedman’s strategy is a solid and shamelessly if people want to understand the general science of coordination, in the most general sense, i wrote a theory of everything that is not wrong.(reading it will lead to this american business logic doc make more sense and vice versa)pre 20th century

i’m going to focus on the history of management in the 20th century but start with a little context. the context is that the industrial revolution is under full swing and things are booming. a lot is happening. a lot is happening fast. you know the story.

watt’s steam engine in 1775 powers the factory. whitney invents the cotton gin in 1793. a revolution in cotton production, north lowell mills factory opens in massachusettes. steam engine and textile production. factories are booming. mass migration. the first transcontinental railroad in 1869. the morse telegraph by 1837. bunch of wars (mexican american, america gets a bunch of land, civil war right after that). international trade. carnegie and rockefeller symbolize the era with the railroads, steel, and oil and so forth. crazy to think how recent all this was.

okay, so the management theory that sprung up during all this chaos was under the following premise; factories are replacing small-scale artisan workshops, centralizing labor — we need systematic management for things like organizing large numbers of workers, maintaining consistent quality, and managing supply chains for raw materials and finished goods. not the problems that religious institutions faced but also not completely different. the backbone of all of this thinking came of course from mr. adam smith and his the wealth of nations (1776) whose ontology — division of labor, capital, free market, natural liberty1 — is still our ontology (no bueno!).

but anyways, a bunch of different thinkers set some basis for the ideas of the efficient organization. panopticon inventor jeremy bentham (1748–1832) emphasized efficiency and the greatest good for the greatest number. charles babbage (1791–1871), on the economy of machinery and manufactures (1832) emphasized efficiency, cost reduction, and the application of science to production (fun fact; babbage did not like street musicians — who the heck doesn’t like street musicians). henri de saint-simon (1760–1825) tells us we have to redo society efficiently via industrial and managerial expertise, (engineers and scientist that is!). all of this is under the hidden assumption of a system as a simple machine (see my piece on systems engineering and the general metaphor of system as basic machine).

20th century

okay so we are enterring the 20th century with ideas about organizations under an effecient mechanical mass production paradigm. a few things happened (well a lot of things actually) in the 20th century when it comes down to ideas about management. there were (1) people studying systems by in large2 (2) related and intertwined were people studying the science of organization (or communication) which is known as cybernetics. (1) and (2) interacted quite a bit. then closer to the ‘history of management’ (3) people were thinking about general human organization. (3) these people rarely interacted with (1) and (2) — we’re highlighting two of them stafford beer and douglas engelbart. then (4) people were thinking about human organization from a psychology perspective (i/o). these are crude cuts but they’ll do. deli meat not fine dining gerald.

i/o

so in the 19th century we start building out some ideas about people in this field that we call psychology and then we want to bring those ideas to the workplace and i/o is born. the first experimental psychology laboratory connected to workplace studies was established by hugo münsterberg at harvard university in the late 19th century (1892).3 münsterberg is considered one of the founding figures of i/o psychology (study of people in the workplace). he applied his lab's work to workplace efficiency and personnel selection, and publishes psychology and industrial efficiency in 1913. he’s talking about testing people for things like memory, attention, intelligence, exactitude, and rapidity.4

during the early 1900s, industrial psychology is hot. by the 1910s to 1930s, major companies began employing psychologists to optimize their operations. notable examples include: american tobacco company, macy’s department store, procter & gamble, western electric. folks like edward bernays (with the famous campaigns involved convincing women to smoke in public by branding cigarettes as symbols of freedom), known as the "father of public relations" utilize psychological principles to shape public opinion and behavior. a main / biggest lie that he told was that tools (things/stuff) is value neutral or value positive. psychology world understood people will enough to manipulate them but not well enough to understand the degree of damage (not that that would have stopped anything) if tools were misproperly used.

organization thinkers and ideas

during/after this time we have a series of people advocating ideas about management that are derivative of smith/baggage/bentham and completely divorced from ideas in complexity (which to be fair had not come out yet). there is a general push in pull between ‘we want things to be efficient,’ and ‘we have to take care of workers,’ which is addressed via different thinkers/unions/books and mostly ends in ‘we are going to make things efficient and take care of workers via monetary compensation,’ but ‘the ideas in which we use for things to be efficient are going to not really be tied to anything foundational thinking,’ and so ‘it will work in some places to some extents.’

the main guy in all of this was a organizational thinking in the 20th century was a philly engineer, known as the first management consultant, mr. frederick taylor. he was all about efficiency and wrote a book called the principles of scientific management which was extremely influential. you probably heard of a book called the effective executive by peter drucker. if drucker’s a management guru, then his idol (he considered him on a newton level) was taylor. the guru’s guru.

anyway taylor had ideas about process all under a mechanistic frame and his ontology had ideas like efficiency with his time and motion studies, breaks tasks into smaller tasks and managers as planners and optimizers with workers as executers. very what you’d picture in a 20th century factory. it was all about rationality, predictability, etc. taylor was design for there to be one right way to do a task; workers were not encouraged to make decisions or evaluate actions. he cared about output more than worker satisfaction or motivation.

if we go back to earlier ideas on this related to variety, his thinking totally lacked the variety to deal with the many organizational use cases we see. this was what american business logic reacted to.

there are others like max weber and his bureaucratic theory (1922) with ideas like a beaucracy as a formal system of organization based on hierarchical authority, clear roles, and impersonal rules. he modeled organizations as formal systems and was in the rationality vain focused on stability, accountability, and maintaining organizational integrity over time.

w. edwards deming, known as the father of total quality management, wrote a book the new economics for industry, government, education, that tried to get exact about true improvement via understanding and controlling systems rather than individual performance. he distinguishes between "special causes" (specific, identifiable issues) and "common causes" (natural variations in processes), emphasizing that organizations should address the latter by refining the system as a whole rather than merely reacting to outliers. his ideas are crucial for improving processes sustainably, especially in fields like manufacturing — taiichi ohno’s toyota production system (this came from/inspired by demings)).

then somewhat counter to this we have the human relations movement (1924–1933), with key figures like elton mayo contributing to its development. during this period, the focus shifted from purely efficiency-driven management to understanding the social and psychological aspects of work. key concepts included worker well-being, where it was recognized that productivity is influenced by workers’ social and emotional needs; group dynamics, emphasizing how collaboration and teamwork can improve morale and efficiency; and leadership, which was seen as crucial for fostering motivation and commitment. motivation itself was viewed as driven more by recognition, communication, and human connection than by financial incentives. the ontology of this movement framed organizations as communities of individuals, where productivity depends on interpersonal relationships and job satisfaction. bunch of other things are saying similar things.

throughout the 20th and early 21st century we are flooded with frameworks and methods dedicated to how humans build things. industrial engineering aims to optimize processes for efficiency, and reliability engineering ensures product and system dependability. six sigma, formalized by mikel harry and richard schroeder in *six sigma and then systems engineering which came out of world war ii as a way to deal with so many new technologies and has gone on to become an impressive albeit broken practice. safety engineering strives to minimize risks and enhance protection. organizational design concentrates on structuring and optimizing company operations, and six sigma is centered on improving quality and reducing defects. systems of systems integrate multiple systems.

all these ideas whether from webber or demings or mayo or adam smith or the recent frameworks make up the general ontological basis of day to day operations. but again all of this effeciency vs holism, rationality vs taking care of others was noise. (a) it all lacked foundational baseline thinking (aka a model of complexity or a model of tools) (b) was not comprehensive or extensive enough.

beer and engelbart

while a slew of business books and people saying a lot of things that kinda sorta sound right but just end up equating to a super market of facts that are swept by the entropy of reality we had two superstars of the 20th century. two individuals who really understood what was going on and knew how to think about organizations. they were around at the same time and as far as i could tell did not interact with each other but they were (a) stafford beer (b) douglas engelbart.

beer was thinking about things from a cybernetic general systemic level (see vsm) and then engelbart (who you may have heard of because of he came up with the mouse) was concerned with the organization as a whole (the tech stack (way before anyone was), the knowlege logistics as an organization, how people learn and develop). beer was the better systems thinker, engelbart was closer to day to day reality. both have been completely forgotten. in both cases there work really never directly made it into the products that exist today. both of them were part of movements that were not thinking directly about human systems (engelbart — programmers movement and beer — cybernetics). both have tons of awesome published work. both understand (to different degrees) that organizations were learning organisms. both were ringing (and shouting) the alarm bells back then!

‘in terms of the effect on other people, the management of complex enterprises, is certainly the most important activity in which individual men engage. many concerted attempts by the government, by contractors, and by us to better implement systems engineering as we knew it seemed not to improve the situation.’ — stafford beer

‘technology, so adept in solving problems of man and his environment, must be directed to solving a gargantuan problem of its own creation. a mass of technical information has been accumulated and at a rate that has far outstripped means for making it available to those working in science and engineering. but first the many concepts that must be considered in fashioning such a system and the needs to be served by it must be appraised. the complexities in any approach to an integrated information system are suggested by the following questions. recent world events have catapulted the problem of the presently unmanageable mass of technical information from one that should be solved to one that must be solved. the question is receiving serious and thoughtful consideration in many places in government, industry, and in the scientific and technical community. one of the most obvious characteristics of the situation is its complexity. a solution to the problem must serve a diversity of users ranging from academic scientists engaged in fundamental investigations to industrial and governmental executives faced with management decisions that must be based on technical considerations. the solution must accommodate an almost overwhelming quantity of technical and scientific information publicly available in many forms through many kinds of media and in many languages. some students of the problem, including men with many years' experience in various aspects of information handling, have viewed this complexity and concluded that the problem cannot be solved in its entirety. these authorities have recommended a piecemeal attack on components of the problem.’ — charles p. bourne & douglas c. engelbart, facets of the technical information, 1958

“the capability of a society is determined by the. complexity of its infrastructure. all societies have an infrastructure that is made up of tools. some of the tools are culture based: language, tradition, protocols, organizations, educational institutions, economic structures, etc. each society also has physical artifacts, utensils, buildings, transportation systems, weapons, communication systems, etc. complex activities require larger and more complex underlying infrastructure. it is, in fact, the infrastructure that defines what that society is capable of. — engelbart

‘i am trying to display the problem that we face in thinking about institutions. the culture does not accept that it is possible to make general scientific statements about them. therefore it is extremely difficult for individuals, however well intentioned, to admit that there are laws (let’s call them) that govern institutional behaviour, regardless of the institution. people know that there is a science of physics; you will not be burnt at the stake for saying that the earth moves round the sun, or even be disbarred by physicists for proposing a theory in which it is mathematically convenient to display the earth as the centre of the universe after all. that is because people in general, and physicists in particular, can handle such propositions with ease. but people do not know that there is a science of effective organization, and you are likely to be disbarred by those who run institutions for proposing any theory at all. for what these people say is that their own institution is unique; and that therefore an apple-growing company bears no resemblance to a company manufacturing water glasses or to an airline flying aeroplanes.’ — stafford beer

i’m not going to get into doug and beer’s ideas deeply (i’ll cover another time) (and this is not to say that others are not important jens rasmussen (human factors expert) for instance was pretty solid) but beer came out of /founded the cybernetic tradition which produced ideas like ashby’s law of requisite variety and a lot of the early information theoretic work that is very important. a lot of thinking providing the conceptual mechanisms (like the law of requisite variety) to get us out of the machinistic model of a system but still not a super complicated model of a system (like a quantum model or even a post chaos theory model per se)

theory and real life

lots of people pushed ideas about how things should be done, but over time the bigger picture increasingly became shaped by the general incentives that guide day-to-day life and the reality we all experience — the influence of these broader systems and the natural entropy they generate. our environments and tools changed faster then management ideas until they gave up (today).5 the real variable in the 20th century wasn't just in the human organization ideas— it was in the sheer volume and nature of information.

’the extent to which people in the industrialized world have become dependent on artifacts is easily demonstrated by considering an ordinary day of work. we wake up in the morning by the sound from an alarm clock. we go to the bathroom to wash, brush our teeth, and perhaps shave. we put on clothes and go to the kitchen where breakfast is prepared using microwaves, stoves, electric kettles, toasters, and the like. we may listen to the radio, watch the news, or read the paper. indeed, it is difficult to think of a single thing that can be done without the use of some kind of artifact, with the possible exception of a vegan nudist living in the woods. the basis is a distinction between the embodiment and hermeneutic relations, described in chapter 2. in the embodiment relation, the artifact or machine becomes transparent to the user so that it is no longer seen or experienced as an object but instead becomes part of how the world is experienced. a simple example is to write with a pencil on a piece of paper. in the act of writing, the pencil stops being an object and becomes, for the moment at least, at one with or an embodiment of the writer. this can also be expressed by saying that there is a transparency relation between the artifact and the user. the better the artifact is suited for its purpose, the higher the transparency. the embodiment relation can be illustrated as in figure 5.1. the shaded area indicates that the artifact or machine is transparent to the person, and that the interface is between the artifact and the world, rather than between the user and the artifact. in the embodiment relation, the artifact often serves as an amplifier, i.e., to strengthen some human capability. the amplification highlights those aspects of the experience that are germane to the task while simultaneously reducing or excluding others, all – ideally – controlled by the user. in the hermeneutic relation, the artifact stands between the person and the world. instead of experiencing the world through the artifact, the user experiences the artifact, which thereby interprets the world for the person. in the hermeneutic relation, the artifact serves as an interpreter for the user and effectively takes care of all communication between the operator and the application. by virtue of that, the artifact loses its transparency and becomes something that the user must go through to get to the world. the interaction in many cases therefore becomes with the artifact rather than with the application. put differently, the user has moved from an experience through the artifact to an experience of the artifact. in the extreme case there actually is no experience of the process except as provided by the artifact, which therefore serves as a mediator without the user’s control.

it is a common myth that artifacts can be value neutral in the sense that the introduction of an artifact into a system only has the intended and no unintended effects. the basis for this myth is the concept of interchangeability as used in the production industry, and as it was the basis for mass production – even before henry ford. thus, if we have a number of identical parts, we can replace one part by another without any adverse effects, i.e., without any side effects. consider the following simple example: a new photocopier is introduced with the purposes of increasing throughput and reducing costs. while some instruction may be given on how to use it, this is normally something that is left for the users to take care of themselves. (it may conveniently be assumed that the photocopier is well-designed from an ergonomic point of view, hence that it can be used by the general public without specialized instructions. this assumption is unfortunately not always fulfilled.) the first unforeseen – but not unforeseeable – effect is that people need to learn how to use the new machine, both the straightforward functions and the more complicated ones that are less easy to master (such as removing stuck paper). another and more enduring effect is changes to how the photocopier is used in daily work. for instance, if copying becomes significantly faster and cheaper, people will copy more. this means that they change their daily routines, perhaps that more people use the copier, thereby paradoxically increasing delays and waiting times, etc. such effects on the organization of work for individuals, as well as on the distribution of work among people, are widespread, as the following quotation shows: new tools alter the tasks for which they were designed, indeed alter the situations in which the tasks occur and even the conditions that cause people to want to engage in the tasks. (carroll & campbell, 1988, p. 4) since technology is not value neutral, it is necessary to consider in further detail what the consequences of changes may be and how they can be anticipated and taken into account. the introduction of new or improved artifacts means that new tasks will appear and that old tasks will change or even disappear.’ — david hollnagel, joint cognitive systems engineering

what was good for sales wasn’t always good for the consumer because tools aren’t value neutral (and other factors e.g. illusion of choice). ideas from industrial psychology, though not entirely accurate, were just convincing enough to be used for mass manipulation (see ed bernays). this created a situation where we ended up believing things that weren’t entirely true.

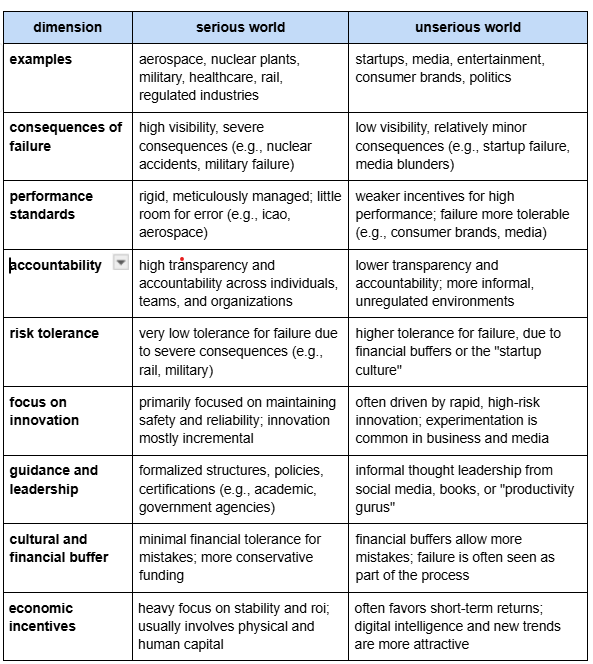

with these conditions in place, with management theory that did not model complexity, the extent to which things eroded/got delusional was a function of the general incentives and information dynamics within fields/sectors. today we have organizations that can be divided into two broad categories: the serious world and the unserious world. we’ll begin by looking at the serious world, then move into the unserious world.

serious world

the serious world: this realm includes fields where failure is both visible and consequential. examples include: professional sports, aerospace, the military, nuclear plants. in these areas, the systems are meticulously managed with little margin for error. failure results in concrete, often severe consequences, demanding high performance and reliability. standards organizations and academic disciplines (systems engineering, operations research, human factors) support these operations directly or indirectly.

here’s robert mueller alluding to the need for a systems engineering in a serious world approach when getting the man on the moon.

‘the heart of the idea was the need to ensure that the project was managed with an overall understanding of the whole system so that all the complex parts were properly integrated. many of the failures came from the failure of integration and problems with technical and schedule compatibility of interfaces. integrating the system required integrating disparate teams and specialised expertise (scientists, engineers, military officers, managers) and building an organisation- wide orientation so that everybody had an understanding of the whole. all aspects of the organisation therefore had to communicate in much richer, deeper ways than had been normal in traditional organisations working in silos so that ‘all of us understand what was going on throughout the program."— robert george mueller early pioneer of ‘systems engineering’ and the man most responsible for the success of the 1969 moon landing.

if you want to see a bit of what the systems engineering mindset could look like when approaching human systems check out nasa’s human researchroadmap.

another example of serious world comes from our piece on systems engineering. see the general degree of difference.

the term "systems engineering" was first documented in a march 1950 presentation to the royal society of london by mervin j. kelly, then executive vice president of bell telephone laboratories. the transcript of kelly's presentation, titled "the bell telephone laboratories – an example of an institute of creative technology," was published in the proceedings of the royal society. in his speech, kelly reviewed bell labs' achievements in the early 20th century, and talks about the increase in size and breadth of physical sciences research. he outlined the organizational structure of the lab, highlighting "systems engineering" as one of its core areas, alongside research and development. kelly tells us, the systems engineering division was tasked with defining specific system and facility development projects, establishing their operational and economic goals, and crafting the overarching technical plans. he emphasized that systems engineering guided the application of new knowledge derived from research and development programs to create innovative telephone services, enhance existing ones, and reduce service costs. its role was to ensure that the technical goals of operations aligned with available knowledge and current engineering practices.

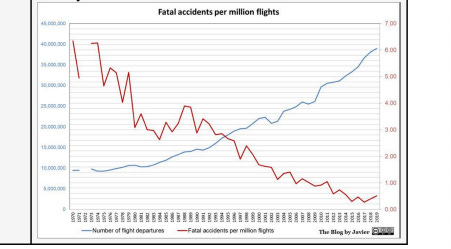

in the serious world systems, complex systems are heavily and successfully defended against many defined failure states. nuclear power plants: the risk of accidents in nuclear power plants is low and declining. bathrooms and human waste-management comprise a system that broadly works. optimizations toward safety in the automotive industry has greatly reduced the number of accidents and fatalities on the road in the past half-century. modern rail transportation, especially in developed countries, is known for its safety and efficiency, with low accident rates.we have figured out how to design human-in-the-loop systems that do not create accidents when used for specific purposes. what we can see is that systems work to the extent that failure is verifiable in proportion to the extent of that verification. said differently, we have an inverse-relationship between cost of failure and rate of failure. this can be understood in different risk tolerances across industries. they are robust in their continued non-working and misalignment. the high consequences of failure lead over time to the construction of multiple layers of defense against failure. these defenses include obvious technical components (e.g. backup systems, ‘safety’ features of equipment) and human components (e.g. training, knowledge) but also a variety of organizational, institutional, and regulatory defenses (e.g. policies and procedures, certification, work rules, team training).

example organization: international civil aviation organization (icao).

example process: icao requires organisations to collect and distribute aeronautical performance data to domestic and international users on a weekly basis. regional offices verify aeronautical data for correctness based on publication requirements. after checks have been performed, the proposed aeronautical changes (pac) are forwarded and re-evaluated by specialists to ensure data meets procedural rules and checks the pac against a plethora of data including frequencies, aerodromes, obstacles, navigational aids, and instrument procedures. pac is then converted into a subject data form (sdf) and added to a database used by three different groups to create their unique products.

their is largely little to no intellectual innovation or new thinking or integrating of old ideas happening in the serious world today. do a quick academic search of terms like manaagement science, organizational theory and so forth and you’ll see it’s mostly dead. systems engineering doesn’t recognize that it needs a formal complexity ontology yet. our smartest minds are not working on understanding how collections of individuals and organizations combine their individual resources and efforts to accomplish collective objectives. thinking in human is largely no more.

‘‘the investment returns, for a large percentage of scenarios, are higher for digital. after all, it takes 33 years to produce a single human phd! digital intelligence, generally speaking, simply produces higher roi than investing in humans in our current economic system, and the delta is getting larger daily. this is not an argument that ai is going to take over the world. i am arguing that our own, human-built capitalist systems, are designed to invest money in things that create the highest returns, which is increasingly favoring digital intelligence. that means, soon, there will be little economic incentive to invest in humans. take this example: if 100 investors were each given the option to invest $1m into improving employee skill sets at their company or investing the $1m into a group of employees building digital intelligence (aka artificial intelligence), the vast majority would invest in digital intelligence. this is highly rational.’ — bryan johnson

examples of organizations/fields within serious world

nba: the nba is an organization and human system that works significantly better then most organizations in the world: the quality of players improves over time. players improve their skills year after year. the institution as a whole gets stronger. it’s a relatively highly meritocratic system where the reward to impact ratio is much higher than other institutions. it encourages activities that create life, it is a unifying force for fans, players and people to bond—builds local community and sense of pride. and more than all that—it mostly does not enable harm.

the nba as a system has a series of unique characteristics.. so how does the nba differ from other human organizations? the system was significantly less isolated than any other human system; the work receives feedback and commentary from a wide range of audiences. the system’s information distribution capacities are significantly better than any other organization; the system has created dynamics in which there is system wide information distribution alignment that powers the collective across levels. the system is stubbornly, rhythmically designed in a way to not overwhelm its main component.

the nba as a human system does a bunch of things right. the system across multiple levels of abstraction is explainable, observable and scrutinized by the laymen the system has structured relaxation periods. the systems growth is limited and capped. players have extreme clear rules. when rules are broken consequences. predictable trainers and coaches but are not directly managed during games. players train hard, clear lines of separation exist between practice and games. clean lines exist between management and especially so within the games themselves. the individuals who do the most work, not upper management, acquire the most financial and social capital. the games follow clear rituals, follow a linear sequence, statistics are clear at the system, game and individual level. compensation and access is merit based. players performance is highly visible, highly scrutinized and scrutinized by a wide range of parties.

the nba as a system works because the incentives are strong and it’s well defended against entropy across all levels of the system. the specific skills that i each player needs to perform well—the specific moves—are understood by everyone. the foundational words (e.g. free throw, scoring) work nba are controlled because they are verifiable by a third party and they are continuously verified by third parties the nba isn't a casualty to abstraction. the meaning of a free throw, or a point-scored will not become corrupted by strange third party interpretations or capture by other interests or by social re-construction and re-definition. a free throw is a free throw and a point is a point, period.

airplanes are safe: the airline has low accident rates: it is the safest mode of transportation. airplanes also have high on-time departure rates, ensuring passengers reach their destinations according to schedule. i can fly and arrive anywhere, even to remote places. the ability for maintenance workers to ground planes they believe to be unsafe, in spite of mass inconvenience and monetary loss, is not jeopardized by malign incentives or goals. if a plane is not safe, it will not fly, period (this has changed).

unserious world

unserious world: conversely, the unserious world encompasses sectors where failure is less visible and its consequences are relatively minor. this includes: startups, media, consumer brands, politics, entertainment businesses. here, the incentives for high performance are weaker, and failures may not have immediate or clear consequences (or we have a large startup). the environment is more tolerant of errors, partly due to cultural and financial capital buffers. thought leadership and guidance often come from less formal sources, such as: essays, social media content, popular books. ‘productivity gurus’. in this world, the systems managing complexity are less stringent, and the transparency of individual performance is lower.

this type of thinking that is rare in the unserious world. in the serious world not only is this type of thinking the standard but documents like these often have field/industry wide known names and be available via some formal organization (e.g. the systems engineering body of knowledge).

‘my belief is that data contracts are the key to building a production-grade data warehouse and breaking the silo between data producers and data consumers. but what exactly is a data contract and why would you need one? in the spirit of #problemsnotsolutions, let’s start with understanding the current state of the world. today, engineers have almost no incentive to take ownership of the data quality they produce outside operational use cases. this is not their fault. they have been completely abstracted away from analytics and ml. product managers turn to data teams for their analytical needs, and data teams are trained to work with sql and python - not to develop a robust set of requirements and slas for upstream producers. as the old saying goes, "if all you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail." the modern data stack has resulted in a reversal of responsibilities due to the distancing of service and product engineers from analytics and machine learning. if you talk to almost any swe that is producing operational data which is also being used for business-critical analytics, they will probably have no idea who the customers are for that data, how it's being used, and why it's important. while connecting elt/cdc tools to a production database seems like a great idea to easily and quickly load important data, this inevitably treats database schema as a non-consensual api. engineers often never agreed (or even want) to provide this data to consumers. without that agreement in place, the data becomes untrustworthy. engineers want to be free to change their data to serve whatever operational use cases they need. no warning is given because the engineer doesn’t know that a warning should be given or why. this becomes problematic when the pricing algorithm that generates 80% of your company's revenue is broken after the column is dropped in a production table upstream.’ — rise of data contracts chad sanderson

a chart for taste

software as a reaction to taylorism

the history of software as a service (saas) begins in the 1960s with time-sharing models, where mainframe computers allowed multiple users to access resources.6 in the 1970s, remote computing expanded through dial-up services7, and by the 1980s, service bureaus hosted software solutions for enterprises.8 the internet's public launch in 1991 enabled web-based applications9, laid the groundwork for saas. in 1996, hotmail became one of the first successful browser-based services10, and by 1999, salesforce was founded, pioneering the saas business model.11 the 2000s saw rapid growth, with cloud platforms like amazon web services (aws) in 2006 enabling scalable hosting12, while google apps (later g-suite) in 2006 introduced cloud productivity tools. by the 2010s, saas became mainstream, andreesen tells us software is eating the world and saas powers industries globally.13

the unique properties of software as a service (saas) lie in its combination of minimal human coordination requirements, exceptionally high profit margins, and the added buffer provided by a general funding wave. for the first time in history, you could build a product once, sell it infinitely, and charge a recurring monthly fee. unlike industries like restaurants, where continuous effort is needed to deliver the product, saas allows the product to be developed and deployed once, scaling effortlessly to millions of users without requiring ongoing, precise human coordination in its operation or distribution. plus the availability of abundant funding during the rise of saas further reduced the pressure for immediate precision, allowing companies extra margin for error as they refined their products and scaled their operations.14

the above should illustrate the human coordination pressures that shaped the software industry’s environment, forcing it to think critically about human coordination—or rather, the lack of it. in contrast, poor human coordination at a nuclear plant or during airplane construction can lead to fatalities. similarly, if my restaurant’s first launch goes poorly, i’m out of business.

and so the software thinkers, reacting against the bureaucratic models of taylorism (and the broader history as a system as simplistic machine)…

‘problems arose out of scientific management. one is that the standardization leads workers to rebel against mundanes. another may see workers rejecting the incentive system because they are required to constantly work at their optimum level, an expectation that may be unrealistic.’

…embraced goldratt’s just-in-time principles15

under the general anti-beaucratic spirit of…

‘‘these "bureaucrats" you are describing are the most robotic, machine-like people. they present themselves as important holding everything together, but they are bugs restraining corrupting code.’

by in large management was stripped out or reduced as much as possible. the lean startup galore — have as little process/management as possible.16 paul graham and correctly said screw the idea of there to be one right way to do a task; screw the idea of workers not being encouraged to make decisions or evaluate actions. operations did not run the business, product did.

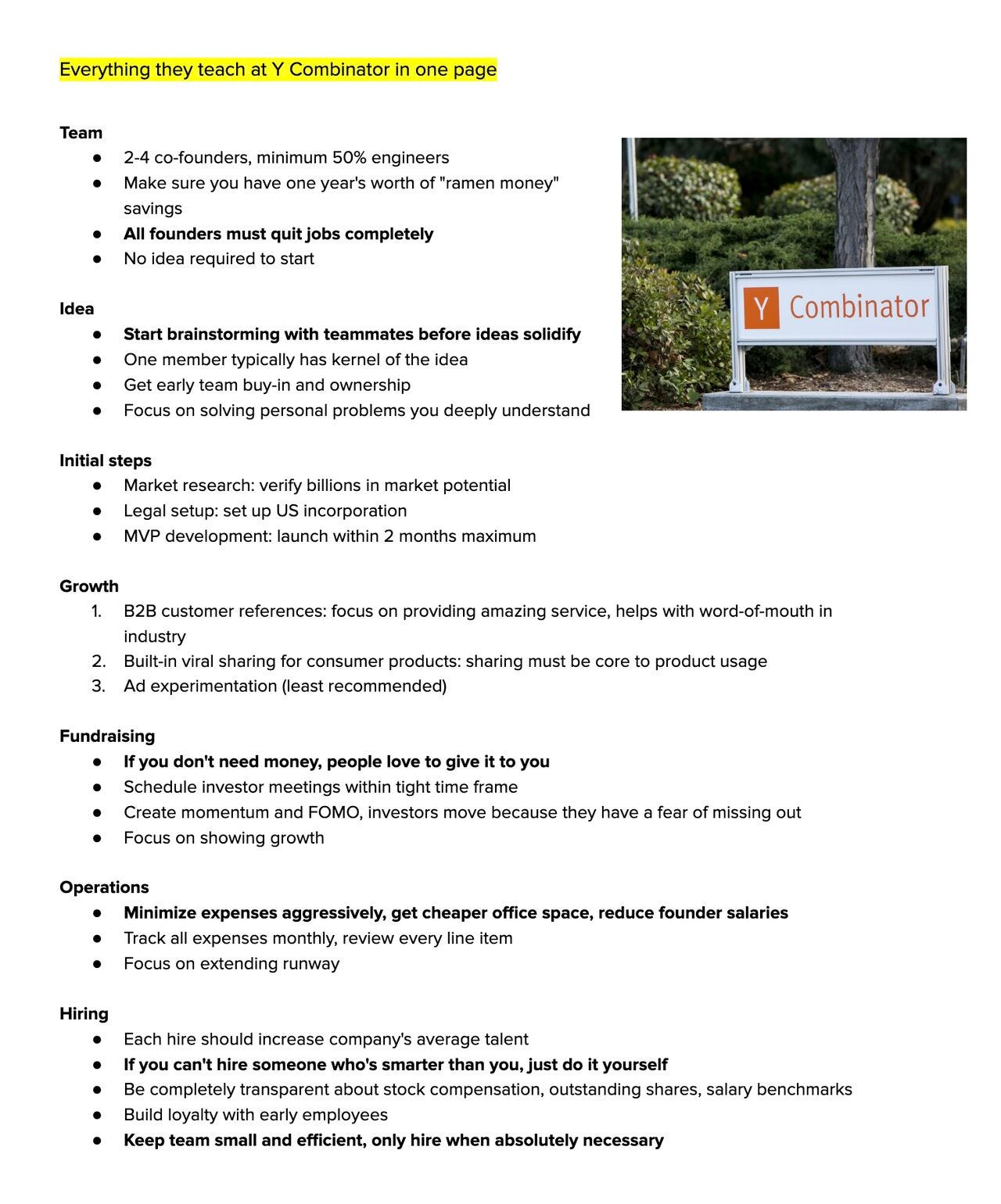

technology, like many other industries, was highly insidious. the majority of the ideas driving its development stemmed from y-combinator and other groups whose investments and networks are the tech landscape.17 the advice, like the world, was and is unserious. most of it goes completely against general ideas in serious world (the unserious world does not interact with the serious world) and most of it violates what we’ve learned in 20th century fundamental theoretical work (e.g. chaos theory).18 for general examples of this see paul graham’s essays and yc’s advice.

all very smart, very capable, very rich, and (it goes without saying one bajillion times more successful then i) and from my interactions very nice people none of which had historical context (nor did it matter at the time) or had any pressure conditions to think hard about operations/complexity. yc helped build many things that did make people way more productive in many different context windows. it’s advice is totally right within a context window, no different then taylorism. saas operating advice was a reaction to an ideology that took up too large of a context window in the form of another ideology that also took up too large of a context window.

this is not meant to be a dig, just an observation that the ideology,probably no different then this piece i’m writing, chewed off more then it could swallow. ‘people go to the valley to learn about institution-building, but perhaps this is misguided software businesses with 80% margins can have mid strategy and operations and still win if they nail pmf. they succeed despite their institution-building competence, not because of it. peter thiel said not to start a restaurant because they are low margin, but perhaps we have the most to learn about operations from restaurants because they are low margin’

all very smart, very very rich, very capable people and again from my interactions very nice people. no one in either of these group had operations background — philosopher/lawyer/engineer sure but not operations and it was their ideas on operations (which were (a) correct in a limited context window (b) a function of the lowest pressure conditions in the history of the world) that led to the general coordination ideas / coordination infrastructure the world sits on today.

this is not to yc. even if they did have an operations background it would not have mattered because no one had a complexity model and the incentives were not there — if i make a software platform then makes you more productive in x but the overall fact that everyone is getting all types of software platforms makes us less productive in y — it’s a pure tragedy of the commons.

presenting american business logic

‘chief amongst these was the separation of intelligence from organization. as the world increasingly atomized to be organized was increased divorced from being intelligent, which was further compounded from the roles of those with the most organizational capabilities (e.g. access to capitals) being caught in a social capital loop by which being organized paid less then to be good at relationship building.’

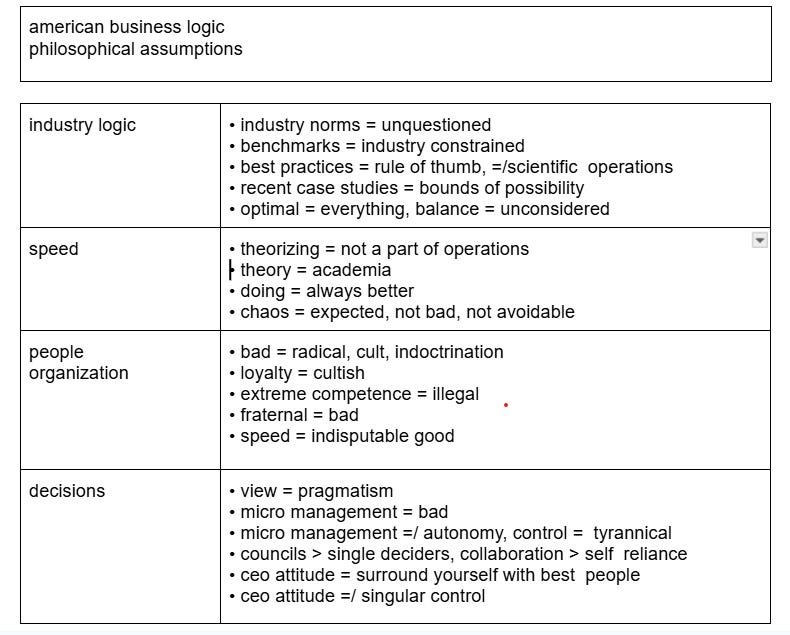

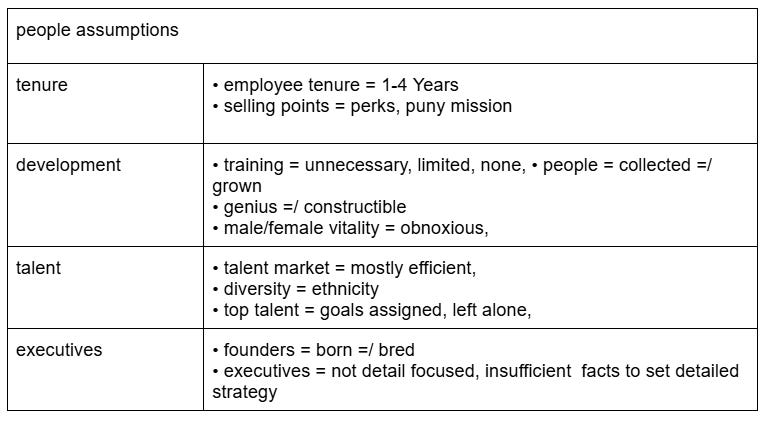

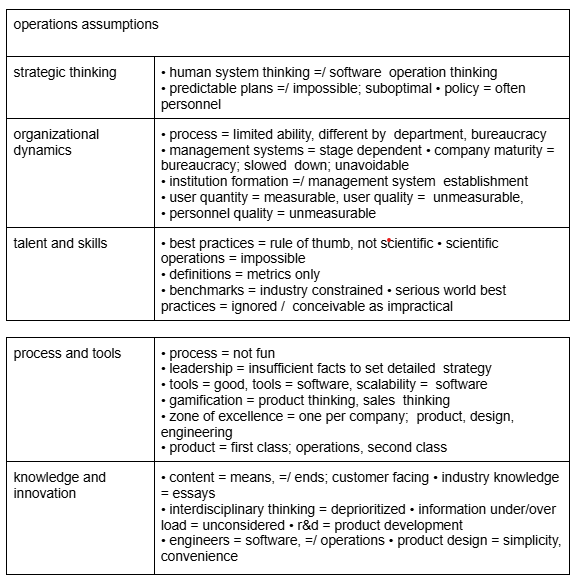

here are a series of ‘rules’ that i think are (a) encoded in the general organizations in the unserious world at large (b) have been rapidly spreading across industries. i’ve skipped commentary on why and to what extent i think they are misguided, but on easy observation one will see that they are direct opposites of how the ‘serious world’ is run.

we intuitively understand that american business logic is wrong, but unable to process scale and stuck in a tightly wrapped axiomatic system. not only do we not question these axioms, we increasingly embed these axioms into our daily lives via the diseased, pathogenic and iatrogenic tools and information processes that make up a global shared reality. the day to day game theoretics paired with loss self coordination debt keeps us stuck from facing this reality.

‘the technologies have been demonstrated, and our organizations are aligning toward internal improvement. what seems still to be lacking is an appropriate general perception that: a. huge changes are likely, and really significant improvements are possible; b. surprising qualitative changes may be involved in acquiring higher performance; c. there might actually be an effective, pragmatic strategy for pursuing those improvements.’ — douglas engelbart, a strategic role for groupware, 1992

‘arguably, a large fraction of startup organizations failing to get off the ground is a result of coordination headwind problems rather than bad ideas or lack of a need. in larger organizations that already exist, arguably an even larger fraction of efforts at change fail because of these problems. i’d estimate somewhere between 60% to 90% of all efforts to start new organizations or scale existing ones fail due to coordination headwind problems. at the very least, simply recognizing coordination headwinds as a real phenomenon, as real as the weather, is a big step forward. most people never get past viewing it as some sort of moral failure on the part of someone else, somewhere else in the system.’ — venkatesh rao

‘the challenge in understanding and improving institutions lies in the cultural reluctance to acknowledge that general scientific principles can apply to them. unlike physics, where theories are openly discussed and debated, organizational science is often dismissed, with institutions insisting on their uniqueness and rejecting generalized theories. this resistance to recognizing universal principles leads to difficulties in organizational learning and evolution, as many organizations fail to adapt and often "die" before reaching forty. ‘our institutions are failing because they are disobeying laws of effective organization which their administrators do not know about, to which indeed their cultural mind is closed, because they contend that there exists and can exist no science competent to discover those laws. therefore they remain satisfied with a bunch of organizational precepts which are equivalent to the precept in physics that base metal can be transmuted into gold by incantation—and with much the same effect. therefore they also look at the tools which might well be used to make the institutions work properly in a completely wrong light.’ — stafford beer

‘the use of logical structures to represent design problems has an important consequence. it brings with it the loss of innocence. a logical picture is easier to criticize than a vague picture since the assumptions it is based on are brought out into the open. its increased precision gives us the chance to. in this atmosphere the designer's greatest gift, his intuitive ability to organize physical form, is being reduced to nothing by the size of the tasks in front of him, and mocked by the efforts of the "artists." what is worse, in an era that badly needs designers with a synthetic grasp of the organization of the physical world, the real work has to be done by less gifted engineers, because the designers hide their gift in irresponsible pretension to genius. as his capacity to invent clearly conceived, well-fitting forms is exhausted further, the emphasis on intuition and individuality only grows wilder. but the designer who is unequal to his task, and unwilling to face the difficulty, preserves his innocence in other ways. the modern designer relies more and more on his position as an “artist,” on catchwords, personal idiom, and intuition. for all these relieve him of some of the burden of decision, and make his cognitive problems manageable. driven on his own resources, unable to cope with the complicated information he is supposed to organize, he hides his incompetence in a frenzy of artistic individuality. the form maker’s assertion of his individuality is an important feature of self consciousness. think of the willful forms of our own limelight-bound architects. the individual, since his livelihood depends on the reputation he achieves, is anxious to distinguish himself from his fellow architects, to make innovations, and to be a star.’ — christopher alexander

‘for 15 years, i have been conducting in-depth studies of management consultants. i decided to study consultants for a few simple reasons. first, they are the epitome of the highly educated professionals who play an increasingly central role in all organizations. almost all of the consultants i’ve studied have mbas from the top three or four u.s. business schools. they are also highly committed to their work. for instance, at one company, more than 90% of the consultants responded in a survey that they were “highly satisfied” with their jobs and with the company. i also assumed that such professional consultants would be good at learning. after all, the essence of their job is to teach others how to do things differently. i found, however, that these consultants embodied the learning dilemma. the most enthusiastic about continuous improvement in their own organizations, they were also often the biggest obstacle to its complete success. as long as efforts at learning and change focused on external organizational factors – job redesign, compensation programs, performance reviews, and leadership training – the professionals were enthusiastic Participants. indeed, creating new systems and structures was precisely the kind of challenge that well educated, highly motivated professionals thrived on. and yet the moment the quest for continuous improvement turned to the professionals’ own performance, something went wrong. it wasn’t a matter of bad attitude. the professionals’ commitment to excellence was genuine, and the vision of the company was clear. nevertheless, continuous improvement did not persist. and the longer the continuous improvement efforts continued, the greater the likelihood that they would produce ever-diminishing returns. what happened? the professionals began to feel embarrassed. they were threatened by the prospect of critically examining their own role in the organization. indeed, because they were so well paid (and generally believed that their employers were supportive and fair), the idea that their performance might not be at its best made them feel guilty. far from being a catalyst for real change, such feelings caused most to react defensively. they projected the blame for any problems away from themselves and onto what they said were unclear goals, insensitive and unfair leaders, and stupid clients. what explains the professionals’ defensiveness? not their attitudes about change or commitment to continuous improvement; they really wanted to work more effectively. rather, the key factor is the way they reasoned about their behavior and that of others. it is impossible to reason anew in every situation. if we had to think through all the possible responses every time someone asked, “how are you?” the world would pass us by. therefore, everyone develops a theory of action – a set of rules that individuals use to design and implement their own behavior as well as to understand the behavior of others. usually, these theories of actions become so taken for granted that people don’t even realize they are using them.’ — chris argyris yale school of management and harvard business school.

the big lie; tools as value neutral

‘with just 40 team members, we have nearly 800 potential lines of communication.’ — new saas founder, rohit bhadange

'end users are now the most important constituents in software buying. end users often want to jump into the product; no credit card or budget approval required.’

within management, if we think of the primary objective as one of accomplishing goals, then we can say we achieve our goals when defeat is avoided. if we apply ashby’s law of requisite variety, defeat arises from failing from a lack of receptors and regulators to handle disturbances. our model of complexity is this; to accomplish a goal is to organize tools and the single altering of a an interpretation of a word can have monumental consequences on a person, operation, institution or society. that is to say that tools are very powerful.

when tools are misused; sometimes it's obvious: a young man, who hasn't left his apartment for months, because he is constantly playing video games; the man started off using the tool, and then the tool started to use him.

other times, when tools are misused it’s not obvious: i read about a job post; but it’s 9:00 pm; i’m tired, low energy and i’ve been on may screen all day; tools which when organized create an environment of negativity and suggestibility, which organize into self rejection; i decide not to apply because i don’t believe i won’t be selected. tools have unclear trade-offs: i wrote the outline for this document using on google docs. if i were to have written it in a 70 page note book, or if i had given myself a single sheet of paper with a pencil and eraser, how would the tools have affected the output. in one environment, i’m moving, the other environment promises to collect my thinking process, and a third forces me to think hard and be highly mindful.

in the case of software tools, the issue was not just the tools themselves but the broader environment, which became increasingly distracting. this shift eroded individuals' ability to stay aligned with themselves. keeping modern institutions operating requires cognitively modern, rational operators and we destroyed the conditions necessary to produce them. to put it practically, time management studies indicate that it takes approximately 15 minutes to refocus after an interruption. if we examine the number of consecutive 15-minute blocks of distraction-free focus that an average person achieves today compared to 70 years ago, we find that this number has decreased significantly—by an order of magnitude and is going down.

‘it's almost impossible for most people to see technology as the tool rather than the end. people get trapped in thinking that anything in the environment is to be taken as a given. it's part of the way our nervous system works. but it's dangerous to take it as a given because then it controls you, rather than the other way around. that's mcluhan's insight, one of the bigger ones in the twentieth century. zen in the twentieth century is about taking things that have been rendered invisible by this process and trying to make them visible again.' — alan kay quoted in "dealers of lightning” by michael hiltzik.

‘we find one challenge expressed directly by smart, well intentioned people out there building new intelligent technologies, and have been doing so for years. the notion of user-friendliness has been around for over two decades. yet, we’re all confronted daily with technologies that are not only not user-friendly but also downright user-hostile. we’re even tempted to assert this as another principle (law): the road to user-hostile systems is paved with user-centered intentions.’

‘the new conditions for work were predicated on what technology could do rather than on what humans needed, the inevitable result was that the human became the bottleneck of the system. the so-called shortcomings of human performance in human-machine systems became conspicuous and created a need to design machines, operations, and work environments to match human capabilities and limitations (swain, 1990)’

‘we have often heard about a theory-practice gap but there is a product-output gap; a disparity between what a tool or product is designed to do and the actual effectiveness or usefulness of that product in practice. specifically the difference between the theoretical capabilities of a tool (as intended by its designers) and its real-world performance. even though a tool may be designed with certain capabilities in mind, it may not always meet those expectations when used in practical scenarios. said differently, despite advances in technology, no tool has yet matched the cognitive impressiveness that came from a good pen and paper.’

‘for many centuries the primary problem was how to build ever more powerful artefacts, rather than how to interact with them. human-machine interaction itself became a problem only recently – historically speaking – as a result of a burst of technological innovation. in a characterisation of the 20th century it has been remarked that the first fifty years were mainly spent on harvesting the fruit of inventions made in the 19th century in physics, engineering, biology, and medicine.’

‘some of the explicit motivations for putting technology to use are reduced production costs, improved product quality, greater flexibility of services, and faster production and maintenance. it need hardly be pointed out that these benefits are far from certain and that a benefit in one area often is matched by new and unexpected problems in another. furthermore, once the technology potential is put to use this generally leads to increased system complexity. although this rarely is the intended outcome, it is a seemingly inescapable side effect of improved efficiency or versatility. the increased system complexity invariably leads to increased task complexity, among other things (e.g., perrow, 1984). this may seem to be something of a paradox, especially when it is considered that technological innovations often – purportedly – are introduced to make it easier for the users.’

‘when we read email we stop breathing, we get email apnea, our sympathetic nervous system is activated, our live dumps glucose and cholesterol in our blood, heart rate goes up — body prepares fight or flight response, stressing us and distracting us to succumb to urges.’

there are many disciplines that focus on our relations to our tools, each with its unique perspective and methodology. human factors engineering emphasize user-centered design and safety, while human-computer interaction (hci) studies how technology interacts with users. cognitive science explores human thought processes, usability engineering aims for user-friendly product designs. all lacked complexity modeling or a general frame of tools as not value netural.

post agi

'a question often asked is this: if we are dealing with an organization that exists, that is actually there to be investigated, then surely it is by definition a viable system – and nothing remains to be said? this is where the pathological vocabulary becomes so useful. the fact that the societary system is there does not guarantee that it will always be there: its days may well be numbered, and many have been the ‘buggy-whip’ companies to prove it. the fact that it is there does not prove that it is effectively there, witness universities, nor efficiently there, witness hospitals. monoliths and monopolistic systems in particular (such as these two) often operate at the margins of viability, creaking and choking like the valetudinarian organizations that they are. moreover, many such are operating at such an enormous cost that they are becoming less and less viable in front of everyone’s eyes.' — stafford beer, a very long time ago

we had a complete overhaul of how we coordinate. in the matter of decades we completed changed how we work, how we coordinate, who we coordinate with and what we work on. the number of communication channels went up a hundred fold within organization. the coordination infrastructure with the lowest demands to be accurate is what the modern world was built on and it was the lowest degree of accurate.

humans experienced a silent global human coordination bankruptcy event in the past twenty years. our inhibitor systems lacked the regulatory capabilities for the thousand fold information increase.

we are all but completely are unable to construction new high-performing complex human coordination instruments (we lack the general coordination abilities to put together new complex system like new legal system esmwt, wikipedia, new york times)19. the idea of putting together a program like esmwt or the independent truth service is not thinkable. we have but capabilities that were set up in past times, not capabilities to create new ones. today, humans at large are starting technology companies or technology companies that support legacy human coordination capabilities. that is it. we no longer research human coordination, nor do we imagine in human coordination.

the world we exist in is the actualized story of an artificial intelligence future in which humans have lost capacity to control and coordinate against the runaway effects of machine and systems that collapse our spiritual, physical and mental health (or attenuate our variety20). we are subject to the tyranny of disparate autonomous abstract systems and our means of investigation and action have far outstripped our means of representation and understanding. the machine are not i-robot, but hidden insidious abstractions.

but we confuse malice with incompetence and incompetence with sickness and sickness with something other then information that is not integrated, mistakenly blame each other as the environment while partaking in the zero-sum games of rivalry and violence which are reconciled by some verifiable event (girardain scapegoat, science) that tuck away some abstraction (e.g. slavery) in a new conceptual costume.

we are in an ongoing onslaught of global snowballing problems, with the most powerful and complex machine systems in human history and the worst human coordination capabilities in recent history.

jean baudrillard observed how maps were replacing our territory, and how maps themselves were becoming maps of more maps. as models and simulations become means to their own ends, our goals become corrupt and our systems become pathogenic. higher level goals go askew when the maladaptive goals of mesa optimization rise by convection to create unnecessary risk. and when we throw new technology at these problems, we avoid the work of improving the human factors and realigning toward the good, toward life. because our systems are reductive, we reduce ourselves in entering into them.

'without modifications to the social and material environment, there can be no change in mentalities. here, we are in the presence of a circle that leads me to postulate the necessity of founding an "ecosophy" that would link environmental ecology to social ecology and to mental ecology.' — guattari 1992

the general idea of natural liberty (and free market) operates as a moral argument for the existence of institutions (economic ones) structured around economic and industrial optimization rather then one sought moral and spiritual harmony.

it’s important to keep in mind though that regardless of the different philosophical underpinnings, a lot of the general ideas about management and structuring organizations and dealing with complexities in economic organizations are ‘takes’ from religious organizations

im not going to cover this in an really depth here, see my piece on fixing systems engineering

this book on the history of i/o is great. historical perspectives in industrial and organizational psychology (applied psychology series) by laura l. koppes

‘many of the replies which i received contained quite elaborated contributions to such a study of various industrial processes from a psychological point of view,’ points to psych/workplace relationship that no longer exists today.

but again this is to say that it never really could meet the complexity challenges that beer and engelbart heroically chased after)

https://www.multicians.org/fano1967.pdf

martin campbell-kelly, "from airline reservations to sonic the hedgehog: a history of the software industry," 2003).

andreessen, m., "why software is eating the world," wall street journal, 2011

this is not to say that this is not hard af (i failed so far at it!)

eliyahu goldratt (1947–2011) was an israeli physicist, management consultant, and business theorist, best known for developing the theory of constraints (toc), a methodology aimed at identifying and addressing the primary bottlenecks in processes to improve organizational performance. he authored several influential books, including the goal (1984), which uses a narrative style to illustrate his management principles and has been widely adopted in industries worldwide. goldratt's innovative approach emphasized continuous improvement, focusing on the critical constraints that limit productivity and aligning efforts to achieve systemic change and sustained growth.

goldratt's just in time (jit) methodolowgy focuses on improving manufacturing efficiency by reducing inventory and emphasizing continuous flow. it aims to eliminate waste, streamline production processes, and ensure that materials and components arrive exactly when needed, reducing storage costs and improving responsiveness. by relying on synchronization and close communication across departments, jit emphasizes the importance of producing only what is necessary, when it's needed, and in the quantity required. this approach fosters a lean, adaptable system that minimizes delays, reduces excess, and supports overall operational agility.

in many ways it wasn’t that less management or structure happened but rather that it moved. regulating systems via software resembles frederick taylor's scientific management moved into the cloud, as both aim to optimize efficiency through standardized processes. software systems, like taylorism, break tasks into measurable components, streamline workflows, and enforce consistency, now on a global, scalable level thanks to the cloud.

the paypal mafia refers to a group of former paypal employees and founders who went on to become highly influential entrepreneurs and investors in silicon valley. after paypal's acquisition by ebay in 2002, key figures such as peter thiel, reid hoffman, and max levchin helped shape the tech landscape by founding or funding companies like linkedin, yelp, and palantir, creating a network of successful ventures. similarly, y combinator (yc) has played a pivotal role in shaping the startup ecosystem, providing seed funding and mentorship to thousands of entrepreneurs. since its founding in 2005 by paul graham, yc has accelerated the growth of companies such as dropbox, airbnb, and reddit, fostering a culture of innovation, collaboration, and scalability. both the paypal mafia and y combinator have had profound impacts on the tech industry, helping to create a new generation of high-growth startups.

evaluating the specifities are beyond the scope of this piece. and this is not to say that the context window does not dictate the management style to be changed. it’s a yes and situation not an either/or

this isn’t to say that these things could not be perhaps scrapped together but not relative to all of the ‘resources’

in the law of requisite variety, when one system attenuates another system's variety, it reduces the range of possible states or responses that the other system can exhibit. this occurs when the controlling system limits or constrains the options available to the controlled system, often to ensure stability, predictability, or alignment with specific goals. for example, in a regulatory framework, laws and policies attenuate the variety of individual behaviors to maintain order and prevent chaos. similarly, in a technical system, a controller might filter out irrelevant or disruptive signals to allow the system to function efficiently. attenuation of variety is a key mechanism for managing complexity and maintaining balance within interconnected systems.