abstract: in this essay, i build on the previous life; a not fake explanation advance piece. i advance the general claim that life is real; or more specifically life a general attribute of all material and non-material systems. i provide historical context to the claim and pictorial examples of items with more and less life. i describe the general properties of life following architect christopher alexander’s framework and discuss the general opportunity for life as a general purpose unifier.1

‘it is always a question of freeing life wherever it is imprisoned, or of tempting it into an uncertain combat.’ — deleuze

‘‘i ended up down a rabbit hole in christopher alexander’s nature of order, book 2 and i need to write about it. i think it’s nothing less than a unifying theory for everything i see working in the world and everything i see failing’.— david gasca, how to make living systems

‘... the ‘life’ which i am talking about also includes the living essence of ordinary events in our everyday worlds ... a back-street japanese restaurant ... an italian town square ...an amusement park ... a bunch of cushions thrown into a corner window-seat ... this quality includes an overall sense of functional liberation and free inner spirit. above all it makes us feel alive when we experience it....it is undeniable – at least as far as our feeling is concerned, that a ... breaking wave feels as if it has more life as a system of water than an industrial pool stinking with chemicals. so does the ripple of a tranquil pond. a fire, which is not organically alive, feels alive. and a blazing bonfire may feel more alive than a smoldering ember.’’ — christopher alexander

‘... we recognize degrees of life, or degrees of health, in different ecological systems ... one forest more tranquil, more vigorous, more alive, than another dying forest ... life occurs most deeply when things are simply going well, when we are having a good time, or when we are experiencing joy or sorrow – when we experience the real...in historic times, and in many primitive cultures, it was commonplace for people to understand that different places in the world had different degrees of life or spirit. for example, in tribal african societies and among california indians or australian aborigines, it was common to recognize a distinction between one tree and other, one rock and another, recognizing that even though all rocks have their life, still, this rock has more life, or more spirit; or this place has a special significance.’ — christopher alexander

‘life is a vitalizing property of all matter. life is in and of all matter. man's concept of life is not logical. man conceives life to be a property apart from matter, quickening compound elements of inorganic matter into living, functioning, organic beings. man defines organic matter as that in which life begins to function, imbuing it with vitality and intelligence, defines inorganic matter as those elements or compounds of matter in which there is no life and in which there is no vitality nor intelligence. man conceives life as spontaneously generated in matter at favorable temperatures and under favorable conditions. life is in and of all things from beginning, always and forever. life is eternal. life is in and of all inorganic as well as all organic matter. life is in and of all of the elements and atoms of the elements and the compounds of the elements.’ — walter russell, universal one

‘can science answer moral and ethical questions? from the time of the enlightenment philosophers have speculated that the remarkable advances of science would one day spill over into the realm of moral philosophy, and that scientists would be able to discover answers to previously insoluble moral dilemmas and ethical conundrums. one of the reasons ed wilson's book consilience was so successful was that he attempted to revive this enlightenment dream. alas, we seem no closer than we were when voltaire, diderot, and company first encouraged scientists to go after moral and ethical questions. are such matters truly insoluble and thus out of the realm of science (since, as peter medewar noted, "science is the art of the soluble")? should we abandon ed wilson's enlightenment dream of applying evolutionary biology to the moral realm? most scientists agree that moral questions are scientifically insoluble and they have abandoned the enlightenment dream. but not all. we shall see.’

‘beauty is traditionally considered to be in the eye of the beholder, meaning that it is subjective, varying from person to person or from time to time. alexander, however, challenged this traditional wisdom, arguing that what we call beauty exists physically as a living structure, not only in arts but also in our surroundings, and it can be quantified and measured mathematically. he further claimed that the quality of architecture is objectively good or bad for human beings, rather than only a matter of opinion. there is a shared notion of beauty among people regardless of their faiths, ethics, and cultures, and it accounts for 90% of our feelings. the idiosyncratic aspect of beauty accounts only 10% of our feelings, and depends on relatively small differences of individual life and cultural history or biology. as alexander claimed, beauty or order coming from a segment of music is no different from that of a physical thing like a tree, since both the music and the tree possess the kind of living structure with far more smalls than larges. both life and beauty come from the same source, the very concept of wholeness. thus, wholeness, life, and beauty constitute a trinity, which is the foundation of the nature of order. — christopher alexander and his life’s work: the nature of order by bin jiang

introduction

in 1944, the celebrated physicist, erwin schrodinger, famously asked, “what is life?” neither schrodinger nor generations of main stream illustrious scientists after him have been able to satisfactorily answer this question. the answer however was satisfactorily determined by architect christopher alexander. alexander was a mathematician turned architect who spent his whole career trying to understand why buildings became so ugly and came to the conclusion that life is a general attribute not simply a biological status.

life is an attribute, not simply a binary biological status. the classic question of the meaning of life fails to recognize that life itself has meaning. life is an objective, measurable attribute inherent in all systems including non-biologically alive and abstract systems. a life perception faculty is intuitive and pre-wired in every human being. life is a scale-free fine grained explanatory mechanism to explain what works and does not work across systems. life as a property enables the required wide diversity of meaning to see that we are more productively alike and diverse than imagined across ideology, time period, ethnicity, and culture.

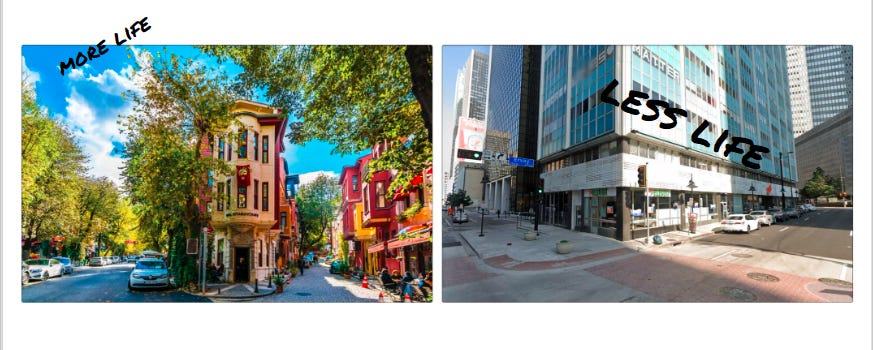

the following pictorial comparison is from max olson’s the grand unifying theory of design. he asks “which street makes you feel more “alive”? what are the patterns in each that contribute to positive or negative emotion? what about good or poor fit with needs?”

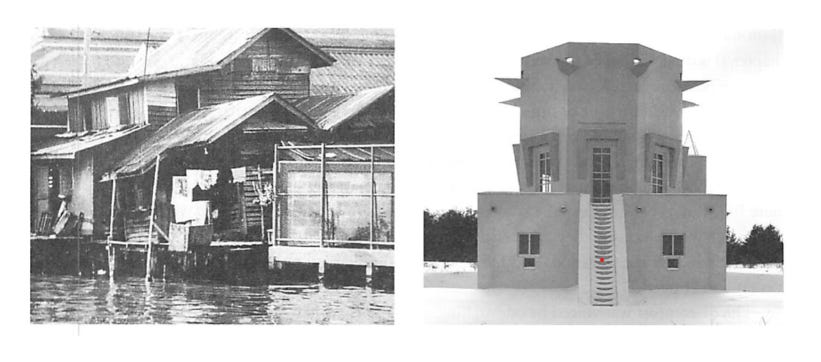

olsen was following christopher alexander’s example in this style of presentation. in 1992 alexander asked 110 architecture students at the university of california which of the following two images had more life:

of the 110, 89 said that the bangkok slum house does, and 21 chose to say the question didn’t make sense or they couldn’t make a choice. precisely zero said that the octagonal tower has more life.

‘for some people the answer was obvious. for others, it was at first not a comfortable question. some asked “what do you mean? what is the question supposed to mean? what is your definition of life?” and so on. i made it clear that i was not asking people to make a

factual judgment, but just to decide which of the two, according to their own feeling, appear to have more life. even so, the question was not quite comfortable for everyone. these students were embarrassed by a conflict between the values they were being taught, and a truth they perceived and could not deny. in spite of themselves, they saw some of the quality of ordinary life, with all the feelings that entails, present in the slum, regardless of its poverty, hunger, and disease.’ — christopher alexander

the two images below are from scott alexander’s essay whither tartaria, in which scott was attempting to understand why art and architecture is no longer beautiful.

the image on the left is harmonious; at a gut level one can literally feel the difference in human care and the subsequent life that went into it. the statue in the right image may be cute. the characters are even animated in movement while being still as stone.

christopher alexander's observation that life is a property of the built environment was less possible to achieve in pre-industrial times because we simply did not create lifeless things in the same way. before the industrial revolution, most objects and structures were made by hand and were inherently tied to human life and activity. the distinction between living and non-living elements was not as pronounced, as the things we created were more organic and interconnected with their surroundings. it wasn't until mass production and mechanization emerged that we began to produce objects and environments that felt disconnected from human presence, making alexander's concept more relevant in the context of modern design.

the lack of human care (human connection or human machine symbiosis) and lifelessness of the right-hand exhibits below, shared by #goodurbanist @wrathofanon on X are self-evident.

and subreddit /r/urbanhell overflows with images such as the following, with its bleak forms, and wash-out of red tail-lights in roads which are taking nobody anywhere.

it may seem, from the examples provided, that perceivers of life will automatically favor antiquity over modernity. this is not the case. modern technology has the ability to produce life as much as it has been, all too often, diminish life.

here are contemporary videos to understand how artists and designers are today handling, or failing to create life. lil yachty with the hardest walk out ever. this scene is full of life, everyone is one. what we can see here is not simply the physical attributes. the music is loud, the crowd is making a lot of noises. lil yachty and the crowd are jumping up and down. what we can see here is that the crowd is alive. we see the same opposite energy in this tomorrowland concert. sunnery james & ryan marciano

the minds behind the world's most successful products understand life at least intuitively. consider this apple commercial for example. to the contrary, the mockumentary hyper-reality by keichi matsuda shows us a fake, sick, weak, fearful, strained, inhibited, noisy technological environment. a story about an environment which is, ultimately, destroyer of life.

life as a creative act

life’s purpose is to create itself, said differently, the human purpose is to create life or avoiding death (or the free energy principle that posits that systems strive to minimize surprise or prediction error by continuously adapting their internal models to align with their environment.).

life is fundamentally a creative act ~ a performance art. it’s here, it’s connects to things and give itself away and then it disappears.

‘software is merely a performance art! a momentary flash of brilliance, doomed to be overtaken by the next wave, or maybe even by its own sequel. eaten alive by its successors. and time...

this is not to denigrate the genre of performance art: anamorphic sidewalk chalk drawings, goldsworthy pebble piles, or norwegian carved-ice-hotels are admirable feats of human ingenuity, but they all share that ephemeral time limit: the first rain, wind, or heat will dissolve the beauty, and the artist must be well aware of its fleeting glory. you can hum a tune you once liked, years later. you can read words or look at a painting from 300 years ago and still appreciate its truth and beauty today, as if brand new. software, by that comparison, is more like soufflé: enjoy it now, today, for tomorrow it has already collapsed on itself. soufflé 1.1 is the thing to have, version 2.0 is on the horizon.’ — kai krause (abridged)

by reading this document the reader is creating. the extent to which the reader creates with the material is a function of the readers process of integrating information (finding fits) or bringing the different elements into a relationship.

others on alexander

‘alexander’s influence also extended far beyond architecture and urbanism. ward cunningham, inventor of wiki (the technology behind wikipedia), credits alexander with directly inspiring that innovation, as well as pattern languages of programming, and the even more widespread agile methodology. will wright, creator of the popular games sim city and the sims, also credits alexander as a major influence, as do the musicians brian eno and peter gabriel. apple’s steve jobs was also said to be a fan.’ —michael w. mehaffy, why christopher alexander still matters

‘christopher alexander's work in the nature of order showed, quite convincingly, that our judgment of life is also innate. he also argued extensively that this innate faculty is deeply entangled with the natural laws of physics, chemistry, biophysics, et cetera.’ — greg bryant,

sarah perry in centers writes about alexander “in the timeless way of building (1979), christopher alexander argues for the counterintuitive proposition that feeling (in the sense of perceiving the beauty and “life” of a space), unlike ideas or opinions, is quite objective; there is an astounding level of agreement between people about how different environments and buildings feel, though there may be little agreement of opinions or ideas about them in general.” perry then cites heavily from the nature of order to make her point. her selected quotations are worth reading in full. it is easy to dismiss feelings as “subjective” and “unreliable,” and therefore not a reasonable basis for any form of scientific agreement. and of course, in private matters, where people’s feelings vary greatly from one person to the next, feelings cannot be used as a basis for agreement.

‘however, in the domain of patterns, where people seem to agree 90, 95, even 99 percent of the time, we may treat this agreement as an extraordinary, almost shattering, discovery, about the solidity of human feelings, and we may certainly use it as scientific. but for fear of repeating myself, i must say once again that the agreement lies only in people’s actual feelings, not in their opinions. for example, if i take people to window places (window seats, glazed alcoves, a chair by a low windows, ill looking out onto some flowers, a bay window...) and ask them to compare these window places with those windows in rooms where the windows are flat inserts into the wall, almost no one will say that the flat windows actually feel more comfortable than the window places—so we shall have as much as 95 percent agreement.

and if i take the same group of people to a variety of places which have modular wall panels in them, and compare these places with places where walls are built up from bricks, plaster, wood, paper, stone... almost none of them will say that the modular panels make them feel better, so long as i insist that i only want to know how they feel. again, 95 percent agreement. but the moment i allow people to express their opinions, or mix their ideas and opinions with their feelings, then the agreement vanishes. suddenly the staunch adherents of modular components, and the industries which produce them, will find all kinds of arguments to explain why modular panels are better, why they are economically necessary. and in the same way, once opinion takes over, the window places will be dismissed as impractical, the need for prefabricated windows discussed so important... all these arguments in fact fallacious, but nevertheless presented in a way which makes them seem compelling. in short, the scientific accuracy of the patterns can only form from direct assessment of people’s feelings, not from argument or discussion.

the degree of life in any given center, relative to others, is, as i have said, objective. but in order to measure this degree of life, it is difficult to use what, in present-day science, are conventionally regarded as "objective" methods. instead, to get practical results, we must use ourselves as measuring instruments, in a new form of measuring process which relies (necessarily) on the human observer and that observer's observation of his or her own inner state. nevertheless, the measurement that is to be made this way is objective in the normal scientific sense... we can always ask ourselves just how a pattern makes us feel. and we can always ask the same of someone else. imagine someone who proposes that modular aluminum wall panels are of great importance in the construction of houses. simply ask him how he feels in rooms built out of them. he will be able to do dozens of critical experiments which “prove” that they are better, and that they make the environment better, cleaner, healthier... but the one thing he will not be able to do, if his is honest with himself, is to claim that the presence of modular panels is a distinguishing feature of the places in which he feels good. his feeling is direct, and univocal. it is not the same, at all, as asking someone his opinion. if i ask someone whether he approves of “parking garages” say—he may give a variety of answers. he may say, “well it all depends what you mean.” or he may say, “there is no avoiding them”; or he may say, “it is the best available solution to a difficult problem”... on and on. none of this has anything to do with his feelings. it is also not the same as asking for a person’s taste.

if i ask a person whether he likes hexagonal buildings, say, or buildings in which apartments made like shoe boxes are piled on top of one another, he may treat the question as a question about his taste. in this case he may say, “it is very inventive,” or, wishing to prove he has good taste, “yes, this modern architecture is fascinating, isn’t it?” still, none of this has anything to do with his feelings. and it is also not the same as asking what a person thinks of an idea. again, suppose i formulate a certain pattern, and it describes, in the problem statement, a variety of problems which a person can connect up with his philosophical leanings, his attitudes, his intellect, his ideas about the world—then he may again give me a variety of confusing answers. he may say, “well, i don’t agree with your formulation of this or that fact”; or he may say, “the evidence you cited on such a such a point has been debated by the best authorities”; or again, “well, i can’t take this seriously, because if you consider its long term implications you can see that it would never do.”... all this again, has nothing to do with his feelings. it simply asks for feelings, and for nothing else.’

alexander was able to argue about the objectivity of a science rooted in human feelings not only by the overwhelming empirical evidence of his results, but also on account of peculiar characterization of just what role human “feeling,” as applied within his experiments with uncanny uniformity and consensus, could play as an instrument of measurement.

‘the degree of life in any given center, relative to others, is, as i have said, objective. but in order to measure this degree of life, it is difficult to use what, in present-day science, are conventionally regarded as “objective” methods.’

in applying his ideas, alexander had to struggle constantly just to give people permission to share their honest feelings, rather than just ad-hoc rationalizations, justifications, or opinions. beneath their egos, he saw, people had a very consistent knack for recognizing life. they could perceive scenes and objects which demonstrated the harmony of the fifteen properties (which follows) even when they were never taught about those properties, or trained how to detect them and their interrelation. but constantly they fought this ability within themselves. their rationalizing mind would get in their way, tying their tongue in order to sound scientific, “objective,” rational, or cultured.

the fifteen properties of life

in the nature of order, alexander argues that there are fifteen properties which are present within all “living” systems of centers within nature and our artificial world. he means this in the most broadly encompassing sense possible—everything in the universe consists of centers, or gestalts, which have developed out of “living” processes, the earmarks of which are these fifteen properties. even though we are innately able to measure the presence of life which proper coordination of these properties bestow upon sensible systems, learning to discern them individually, and their interplay, takes a great deal of perceptual training; moreso to employ them and bring them to life within one’s own design. each is simple, but together they are complex enough to explain everything you see, hear, and touch.

everything living has boundaries. everything living has local symmetries and alternating repetitions of form. everything living evinces roughness and contrast, and echoes its features across its form and through its levels of scale. gestalts interlock within one another, like puzzle pieces, and each side presents a positive definition of space. there are voids, and there are simplicities and inner-calmness. there is good shape, gradient, and “not separateness.” all of these features enhance living constellations of strong centers which, to our human perception, can be said to appear the most living. these properties alexander finds in all areas of nature, at all sizes. they are in waves and estuaries, in snail shells and leaves, in the arms of galaxies and in rocks. and paintings, rugs, pottery, ornaments and buildings from all traditions, east and west can, too, be analyzed and judged by the sensible presence of and harmony within all these mutual reinforcing properties.

centers are the wholes about which everything organizes, so-called because they don’t necessarily have boundaries as shapes or figures do. they aren’t like physical centers of gravity, but rather exist in stress patterns within the field of their relation to other centers. centers are recursive, and while each center can be considered a whole on its own, it also contains wholesome centers within itself, while simultaneously supporting other centers in forming greater wholes. and it is in experiencing the wholesomeness of our world, natural and human-made, that humanity finds the grounds of itself, its own base wholesomeness, the sustaining roots of life. all the processes of nature have created, across strata, the fifteen properties within all material forms. good human design, alexander advises, has traditionally followed its own sense of those same processes to create human culture and human environments. however, as he writes in the nature of order,

we have suffered, in the last hundred years especially, because the old roots of architecture—its sound pre-intellectual traditions—have largely disappeared, and because the lawless, arbitrary efforts to define a new architecture—a modern architecture—have been, so far, almost entirely without a coherent basis... the essence of the problem is that we have not, as far as i know, ever yet concentrated our attention on the fact that in nature, all of the configurations that do occur belong to a relatively small subset of all the configurations that could possibly occur... in nature the principle of unfolding wholeness creates living structure nearly all the time. human designers, who are not constrained by this unfolding, can violate the wholeness if they wish to, and can therefore create non-living structures as often as they choose.

in purely mathematical terms, the number of possibly ugly, post-modern, inhospitable architectural designs which could be created, or generated, greatly dwarf the possible number of life-sustaining, wholesome designs. this is true, just as the number of randomly generated songs, or noisy, senseless images which could come created vastly outnumber the amount of beautiful or sensible ones which make-up our cultures of music and graphic art.

by distilling and focusing on what it is which makes good building-designs wholesome, alexander proposes a mode of perception and criticism which he sees can be extrapolated, in some way, into all domains. the ability to differentiate, quantifiably, the amount of “life” within any proposed form is his prescription for setting-right every field of human creation within society. it may be easy for the reader to assume that what is being described here is something of a universal aesthetic; something like a guide, drawing on nature, for creating or criticizing art. where alexander challenges us most, however, is in his insistence in calling this system “life.” as we’ve seen, he calls it objective, and, furthermore, situates it as a science at home within the domains of physics and biology. verifying this is a matter for your own empirical research. the reader is invited to read christopher alexander, and accept his challenge in seeing the world through his eyes for a while. putting on the glasses which reveal a perceptual world of life-giving forms, in order to evaluate first-hand the experience of a living universe, is the means by which we encourage everyone to escape the all-too-rigid appreciations of what “life” truly is as described by biology or ai theorists. this is essential because, as alexander observes again and again in his discussions with those who inhabit the buildings and urban areas he designed and studied, living environments facilitate human wholeness in its base form. the human subject, himself or herself, becomes wholesome and potent as an agent within a life-nourishing, living environment. where these fifteen properties exist in mutual reinforcement, people are empowered to find themselves and their higher humanity, to become themselves again. and this goal, the restoration of common humanity, is a goal which the living principles foundation seeks to work toward.

different conversations about life

christopher alexander helps us step outside the still-current notion of life as purely a biological phenomenon, but he is of course far from the first person to propose such a larger definition. alexander’s concept of life was largely inspired by philosopher alfred whitehead, who also went beyond the biological meaning. concerning life, ideas like this have existed throughout history. in historic times, and in many primitive cultures, it was commonplace for people to understand that different places in the world had different degrees of life or spirit.

‘for example, in tribal african societies and among california indians or australian aborigines, it was common to recognize a distinction between one tree and another, one rock and another, recognizing that even though all rocks have their life, still, this rock has more life, or more spirit; or this place has a special significance.’ —christopher alexander

although such a conception does not yet exist in modern science, it does exist in traditional buddhism, which in many sects treats the world in such a way that every single thing “has its life.” many animistic religions too—for example, those of african tribes, or of the australian aborigines—treat each part of the world as having its own life and its own spirit.—christopher alexander

it is only in the modern tradition since the enlightenment that this notion of a living universe so homogeneously fell out of favor. alexander fingers descartes as the central figure inaugurating the metaphysics which presupposes the universe as a grand clockwork mechanism. exceptions to this metaphysics have been few until late, but never zero. the modern western tradition has still occasioned attempts to restore vitality to its cultural perception—those works in the vitalist tradition, for example, by goethe, hans driesch, and most notably henri bergson’s l'évolution créatrice in 1907.

most recently, it is in speculative realism that one finds today’s challenge to the cartesian philosophy of cause and effect which characterizes western philosophy. illustrative of this approach is the vitalism expounded by eugene thacker. we’ll allow the collaborative editors at wikipedia to provide the quickest overview.

eugene thacker has examined how the concept of “life itself” is both determined within regional philosophy and also how “life itself” comes to acquire metaphysical properties. his book after life shows how the ontology of life operates by way of a split between “life” and “the living,” making possible a “metaphysical displacement” in which life is thought via another metaphysical term, such as time, form, or spirit:

"every ontology of life thinks of life in terms of something-other-than-life...that something-other-than-life is most often a metaphysical concept, such as time and temporality, form and causality, or spirit and immanence."

thacker traces this theme from aristotle, to scholasticism and mysticism/negative theology, to spinoza and kant, showing how this three-fold displacement is also alive in philosophy today (life as time in process philosophy and deleuzianism, life as form in biopolitical thought, life as spirit in post-secular philosophies of religion).

thacker examines the relation of speculative realism to the ontology of life, arguing for a “vitalist correlation”:

“let us say that a vitalist correlation is one that fails to conserve the correlationist dual necessity of the separation and inseparability of thought and object, self and world, and which does so based on some ontologized notion of ‘life.’”

ultimately thacker argues for a skepticism regarding “life”:

“life is not only a problem of philosophy, but a problem for philosophy.”

other thinkers have emerged within this group, united in their allegiance to what has been known as “process philosophy,” rallying around such thinkers as schelling, bergson, whitehead, and deleuze, among others. a recent example is found in steven shaviro's book without criteria: kant, whitehead, deleuze, and aesthetics, which argues for a process-based approach that entails panpsychism as much as it does vitalism or animism. for shaviro, it is whitehead's philosophy of prehensions and nexus that offers the best combination of continental and analytical philosophy.

another recent example is found in jane bennett's book vibrant matter, which argues for a shift from human relations to things, to a “vibrant matter” that cuts across the living and non-living, human bodies and non-human bodies. leon niemoczynski, in his book charles sanders peirce and a religious metaphysics of nature, invokes what he calls "speculative naturalism" so as to argue that nature can afford lines of insight into its own infinitely productive "vibrant" ground, which he identifies as natura naturans.

life as a unifier

the quality of our society is the quality of our invisible infrastructure.2 our key institutions, governments, providers and overseers of said infrastructure have concluded that society is to be organized under two metrics: (1) life expectancy (2) gdp3, gross domestic production. said differently, the goal of society is for people not to die, and the consumption or production of goods, is how society measures life. life, however, is an objective attribute of all material systems.4

at the core of alexander’s vision is the recognition of shared commonalities—what unites us as individuals and groups outweighs the differences we often focus on. life itself is a unifying property, allowing for the coexistence of varied meanings while enabling productive diversity. it serves as a bridge between scientific and religious worldviews, encompassing concepts like freedom, vitality, and interconnectedness.

formalizing the goal of increasing/preserving life has the potential to solve all those problems of alignment. everyone shares this same goal implicitly because everyone wants to build a better future for our children! yet, sometimes it appears that misalignment increases as much as agreement. we know that the current metrics aren’t strong enough to align us. life is.

some final thoughts on life: measuring life and life as verifiable

until recently, science was not yet in a state ready to appropriately consider or verify life as we’ve been describing it. a great deal of christopher alexander’s work has entailed explaining the history of science in order to explain why this is so.

‘the mechanistic idea of order can be traced to descartes, around 1640. his idea was: if you want to know how something works, you can find out by pretending that it is a machine. you completely isolate the thing you are interested in—the rolling of a ball, the falling of an apple, the flowing of the blood in the human body—from everything else, and you invent a mechanical model, a mental toy, which obeys certain rules, and which will then replicate the behavior of the thing. it was because of this kind of cartesian thought that one was able to find out how things work in the modern sense. however, the crucial thing which descartes understood very well, but which we most often forget, is that this process is only a method. this business of isolating things, breaking them into fragments, and of making machine-like pictures (or models) of how things work, is not how reality actually is. it is a convenient mental exercise, something we do to reality, in order to understand it.

descartes himself clearly understood his procedure as a mental trick. he was a religious person who would have been horrified to find out that people in the 20th century began to think that reality itself was actually like this. but in the years since descartes lived, as his idea gathered momentum, and people found out that you really could understand how the bloodstream works, or how the stars are born, by seeing them as machines—and after people had used the idea to find out almost everything mechanical about the world from the 17th to 20th centuries—then, sometime in the 20th century, people shifted into a new mental state that began treating reality as if this mechanical picture really were the nature of things, as if everything really were a machine.

‘but instead of lucid insight, instead of growing communal awareness of what should be done in a building, or in a park, even on a tiny park bench—in short, of what is good—the situation remains one in which several dissimilar and incompatible points of view are at war in some poorly understood balancing act.’ — christopher alexander

alexander’s account of the effects of the enlightenment is one widely held and corroborated by many thinkers, past and present. the invention of “science” or the scientific method in the west first arrived when “natural philosophy” supplanted the authority of the catholic church by provably refuting biblical scripture through empirical evidence and replicable prediction. rather than try to find narratives that harmonized with a prescribed doctrine of cyclical nature, the impetus of scientific inquiry was open-ended, linear, and never complete. it was promethean in its challenge to the authority of the gods, in effect putting the interests and curiosity of mortals above those of the “gods” or ecclesiastical authorities. this insubordinate “skepticism” accentuated the separation of man from nature.

galileo was the first to make his argument in mathematics, base his conclusions on empirical observations, and to argue for the invariance of motion in different inertial frames, thereby setting the foundation for newton’s classical mechanics. this shift was to establish a new form of “empirical authority” and “evidence,” a fundamental premise of the scientific method.

it was this very independence from any form of doctrinal compliance that gave enlightenment science its energy, freedom, power, and eventual credibility. very quickly, this new intellectual and eventual institutional freedom resulted in a cascade of discoveries and practices with the founding of the royal society in london in 1660. through the collaborations of robert boyle, francis bacon, robert hooke, and many other ‘free thinkers’ of the time, the influence of the royal society culminated in the presidency of sir isaac newton in 1703. its motto, nullius in verba, “take no one’s word for it,” appropriately expressed its commitment to facts and evidence.

once “natural philosophies” became testable and subject to the proof of counterfactuals, they not only moved the needle of verification from the “like” of metaphorical reasoning to the “is” of scientific proof; they made possible the design of material artifacts, indeed, technologies, that translated the potential of scientific findings into affordances to serve human needs and vanities. there was a clear divide between the material and the immaterial; the former being the provenance of science and the latter of metaphysics and religion.

derision. then came information theory, cybernetics, and digital and computational technologies that quickly spilled over into physics, complexity sciences, biology, and neuroscience. —autonomous culture making: sentient media for quantum narratives, from uncertainty studios, john h. clippinger, ph.d., peter hirshberg obe

this is a subject which has been discussed across countless fields, leading to a wide range of conclusions. expanding the scope of science without abandoning objectivity requires continuing these vital conversations. the experiences and successes of alexander in advancing such discussions during his lifetime are invaluable to these efforts.

in today’s scientific worldview, a scientist would likely reject the idea of a wave breaking on the shore as a living system. if told that this wave possesses life, a biologist might respond, “you mean because it contains micro-organisms or perhaps a crab?” but this is not the claim being made. instead, the suggestion is that the wave itself—a system currently viewed through the lens of hydrodynamics—has a degree of life. moreover, this perspective implies that every part of the matter-space continuum possesses life to some extent, with variations in intensity.

in the 20th-century scientific paradigm, life was largely confined to the study of individual organisms—systems capable of reproduction, self-healing, and stability over a defined lifetime. questions arose, such as whether a fertilized egg is alive in its earliest moments or whether a forest as a whole is alive. during alexander’s later years, science began shifting toward an orientation more receptive to verifying and objectively understanding life’s broader definitions.

today’s scientific vocabulary often excludes terms like “alive” for systems outside traditional biological definitions, yet such systems undeniably play a vital role in the broader life of larger ecosystems. adhering strictly to a mechanistic view of life risks reducing ecological systems to simplistic preservationist ideals. however, alexander argued that life is embedded within the structural fabric of space itself, which can be analyzed mathematically and physically. although mathematics was insufficient to fully capture the concept of “wholeness” during his time, alexander used visual examples from nature and human creation to communicate his ideas. recently, mathematical models have emerged capable of quantifying beauty and life in structures.

alexander’s work in the nature of order focused on understanding and creating complexity and life in both nature and human environments. the series emphasizes not just order but also life and beauty, addressing how we can create surroundings rich in these qualities.

since alexander, these expanded ideas have been taken up by many, who continue to build upon them. integrating research and sharing developments is now a top priority for advancing our understanding of life.

there has also been progress in extending the concept of life to ecological systems. while such systems may not meet the classical definition of life, they are undeniably intertwined with biological life. with advances in quantum mechanics, computational biology, and related sciences, the boundaries between matter, energy, and information have blurred. even the role of the observer is now questioned, influencing fields ranging from quantum theory to evolutionary biology.

concepts like the free energy principle and active inference suggest that mind exists across various forms and scales, blending material and immaterial aspects. this approach represents a new, testable paradigm, distinct from older religious or philosophical notions of mind. thinkers like teilhard de chardin, whose ideas of the noosphere prefigured the internet, align surprisingly well with modern scientific developments.

michael levin’s work, for example, touches on consciousness and cognition in ways reminiscent of panpsychism but diverges in key areas. he avoids philosophical labels, focusing instead on pragmatic research into hierarchical cognition, from cellular to complex systems. this pragmatic approach aligns with the goal of integrating biological insights without veering into abstract debates.

instead of the fragmented, lifeless aesthetics of postmodern architecture and anti-human technologies, the possibility of aligning life across material forms offers hope for society. life thrives on diversity, with its strength found in meeting evolving demands across environments. the ability to detect patterns within living systems does not constrain diversity but enables it, much like the finite elements of chemistry produce endless molecular possibilities.

diversity is a hallmark of human life, defined not by uniformity but by the coexistence of countless unique ideas, abilities, and perspectives. humans defy traditional evolutionary patterns by evolving through shared ideas rather than genetics alone. this horizontal evolution underscores our capacity for creativity and connection across differences.

general notes: (a) some of the writing in this piece was done by clinton ignatov (b) the notion that life is the physical emergent interface that symbol grounds consciousness is important and not discussed (c) the fact that we have extended christopher alexander’s definition to say that abstract systems have different degrees of life is important and not discussed

the quality of our society is largely conditioned by the quality of our invisible infrastructure. infrastructure often means the hidden pipes and circuits and tunnels which, behind walls and screens and asphalt, splice our world together from behind. while these affairs of our physical environments are especially important, they can only be handled once we’re on the same footing regarding our common meaning, standards and definitions. it is these which we refer to here as “invisible infrastructure.” they are the constituents of the human systems: the social patterns of organization and constructs which give us shared meaning and common goals to work toward, together.

our key institutions, governments, providers and overseers of said infrastructure have organized a great deal of our society around a) metrics and, b) goals for those metrics. first and foremost, a great deal of infrastructure is organized around life expectancy, which is easily measured and for which goals are set. and, yet, there are no like-terms agreed upon to measure and target the quality of the time when we are expected to live for! let us run through the range of the many competing standards and measures:

psychologists often use subjective well-being (swb). life satisfaction: individuals rate their overall life satisfaction on a scale.

we use income and economic indicators: gdp per capita, personal income, and economic stability.

things like employment and job satisfaction: employment rates, job security, and job satisfaction.

we use health metrics: life expectancy, disability rates, and overall health.

we use things environmental quality: air and water quality, access to green spaces, and exposure to environmental hazards.

we use cultural indicators: cultural engagement: participation in cultural and recreational activities.

things like educational attainment: levels of education achieved. educational satisfaction: satisfaction with the educational experience.

political indicators: stability of the political environment. access to political rights: access to democratic processes and political rights.

personal safety: crime rates, personal safety, and perceptions of safety.

national security: security at the national level.

technology and innovation: access to technology: availability and access to modern technology. innovation: a culture of innovation and technological advancement.

and social indicators: social relationships: quality and quantity of social connections, relationships, and support networks.

and it goes on. the point however though is that the scale of metrics collectively ignore the fact that life is.

since life is an attribute of all these systems, and since we now have a good definition of life, are there ways to rectify all these questions toward one end? that of life itself? we are proposing nothing less than that an increase of life, defined above, become the unifying metric-as-goal for system performance and explanatory mechanism of what works and does not across all relevant systems and domains. non-transient, unnatural states of decay in society are undesirable, a sentiment universally acknowledged. does not the world collectively agree and express a common desire for a thriving environment where our children can flourish? acknowledgment of life, and the cycle of life and death, resonate with everyone. regardless of location or cultural background, everyone can at least identify and agree when something is biologically dead. clarity on the opposite, being alive, is equally universal, as alexander's empirical work reveals. this is what is new. the presence of life in its biological sense is tangible reality, we’ve long known. and yet, for all that, the larger definition of life we are grappling with here has remained elusive and confusing to this very day. ask around! what is the meaning of life? despite our global interconnectedness, agreement remains elusive. different perspectives from individuals worldwide underscore the challenge of finding a common understanding. yet across the world, a growing number of responsible minds are acknowledging the magnitude of this problem, recognizing that without a shared understanding of life's meaning, global collaboration and the creation of a better future for our children become increasingly challenging.